Brussels (Belgium), Beni (DRC), Bukavu (DRC), June 10, 2020

Reading time:

14 min

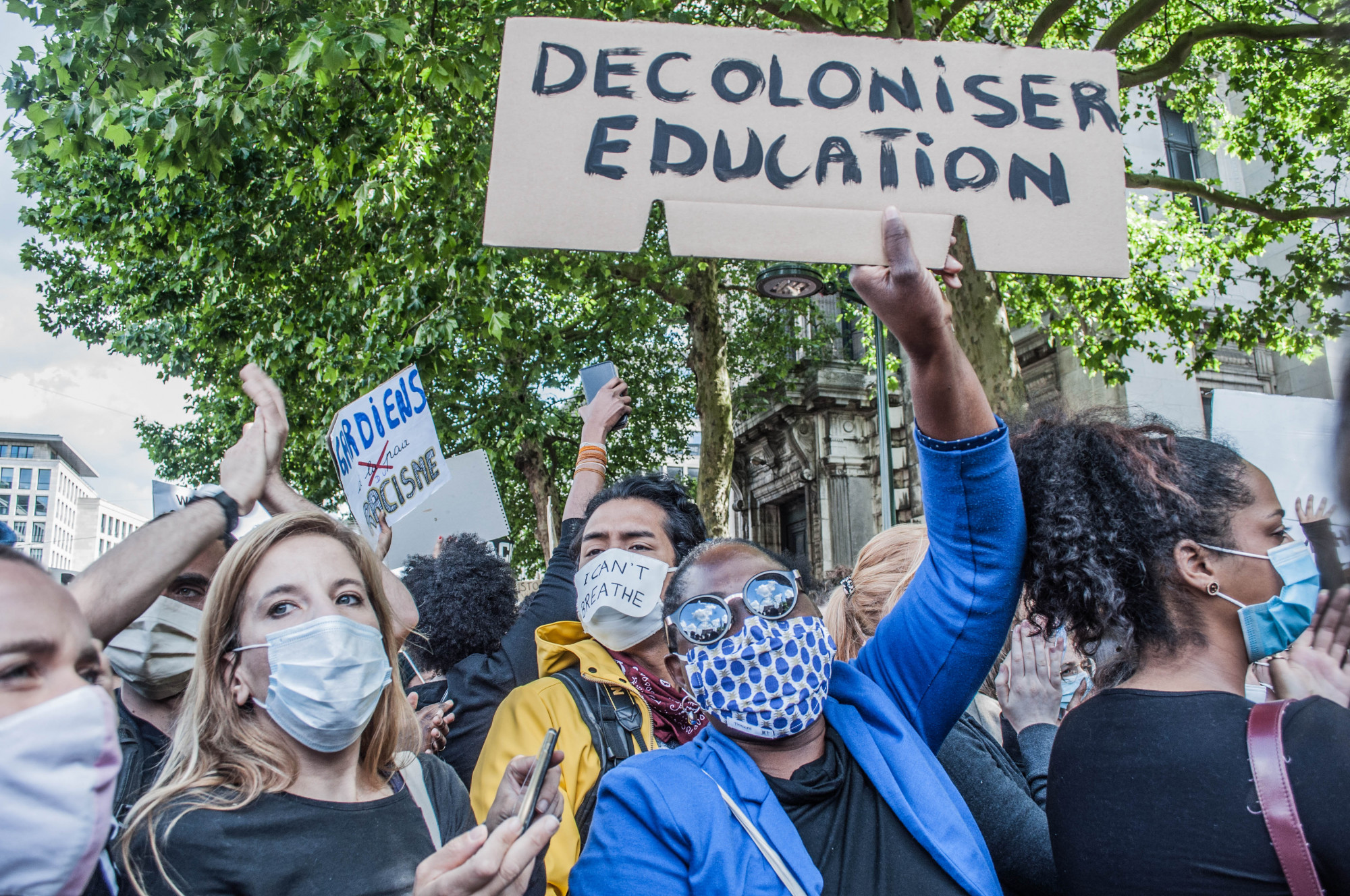

A crowd climbed on one statue in Brussels over the weekend and waved the Congolese flag while chanting “murderer” and “reparations”. The movement is gaining traction with more than 60,000 people signing a petition calling for the removal of all King Leopold statues.

Such statues are viewed by protestors as symbols of white oppression and slavery and have become focal points during recent demonstrations, with protestors in the US and UK defacing or tearing them down.

On June 30th, Congo will mark 60 years of independence, but in all that time, there has been no justice for the crimes of colonialism. Some have compared King Leopold to Hitler and Stalin and debate continues over whether he committed genocide. From 1885 to 1908, he ruled Congo as a private fiefdom at the start of perhaps the most brutal and exploitative of colonial regimes, which lasted for 75 years until 1960. Under Leopold, Congo’s population was “owned” and enslaved by the king, who looted ivory and ordered severe punishment for those who did not meet the quota for rubber production. Punishment included the cutting off of hands, a practice documented by the missionary photographer Alice Seeley Harris. Her photographs inspired Mark Twain to write his anti-Leopold satire King Leopold’s Soliloquy published in 1905. Leopold’s imperial exploitation also inspired Joseph Conrad’s novel Heart of Darkness, first published in 1899.

Belgium’s history of imperial violence does not feature strongly in the country’s educational curriculum or in public discourse, and King Leopold is generally celebrated for bringing civilization, welfare, and culture to Congo. A U.N. Security Council panel of experts said in a report last year that racial discrimination was “endemic” in Belgium’s institutions and called on the country to confront its colonial past “in order to tackle the root causes of present-day racism faced by people of African descent”.

Belgium’s influence over Congo did not end with independence. It was involved in the assassination of Patrice Lumumba, Congo’s first legally elected prime minister, who was executed by Belgian and Congolese forces on January 17, 1961. The bodies of Lumumba and his two associates were thrown into shallow graves before a Belgian police officer later led a group to the graves where the bodies were dug up, hacked to pieces, and dissolved in sulphuric acid, with any remnant set on fire. Belgium apologized in 2002 for its role in Lumumba’s killing, expressing “its profound and sincere regrets.”

Belgium also apologized last year for kidnapping thousands of mixed-race children from Congo between 1959 and 1962. Belgium’s colonial-era segregation laws banned interracial marriage, and children born from a Congolese mother and Belgian father were considered to represent the abuse of those laws and shipped away.

In 2018, a $73 million overhaul of Belgium’s Africa Museum, a former colonial institution holding one of the world’s largest collections of African art, attempted to address some of the historic injustices, but instead led to calls from Congo’s government for many of its artefacts to be repatriated.

The most popular chant among the Congolese protesters on Sunday was “We Want Justice for Congo”. What that justice might look like is hard to say. At the very least, Belgium must acknowledge what it did in Congo, confront the endemic racism described in the UN report, put Belgium’s colonial history on the school curriculum, repatriate stolen artefacts, and relocate those statues and monuments in museums rather than in public spaces.

On Tuesday, a 150-year-old statue of King Leopold was removed in Antwerp and taken to the Middelheim Museum after protesters defaced it with red paint. But in a reflection of the difficulties of confronting Belgium’s imperial history, Antwerp’s mayor, whose right-wing party has pushed for a crackdown on immigration, said the damaged Leopold statue was removed because it was a “public safety issue” and suggested that it might be restored, even if it was not put back in place.

“Taking down statues is important on the symbolic level, but it is just the beginning,” Joëlle Sambi Nzeba, a spokeswoman for the Belgian Network for Black Lives told the New York Times, adding that even she as a Belgian-Congolese had to educate herself about the colonial atrocities. “Those monuments are present not just in public space, but also in people’s mentalities.”

We as Congolese must also do something to improve our own situation. We’ve had decades of conflict and much of it is driven by inter-communal violence and animosity between different groups. It is about power and the monopoly of power—whether political or economic—along ethnic and racial lines. This is what that drives the hate and the massacres that we are still seeing in Congo today.

The government hasn’t been able to stop the killings going on in eastern Congo and when activists protest the lack of security, they sometimes end up on the receiving end of violence. Two weeks ago, Freddy Kambale, an activist with the non-violent youth civil society movement Lutte pour le changement (LUCHA), was shot and killed by police during a protest in Beni.

Heavy-handedness by police also led to the death of a teenager in Bukavu over the weekend. The city’s youth regularly organize a Sunday run through town to keep fit, but the activity was banned due to coronavirus restrictions. To disperse the crowd, police opened fire with live rounds (see video) and tear gas. Mutambo Bulambo Bienfait, 17, was killed in the stampede as people fled, according to local media.

Police violence in Congo is not something new. At least 27 young men and boys were killed in custody during an anti-crime campaign last year, according to Human Rights Watch, which said victims were strangled, shot, and disappeared from custody. And in April, police in western Congo repeatedly used excessive lethal force against a separatist religious group, Bundu dia Kongo, killing at least 55 people and wounding scores more, according to HRW.

So if we are calling for justice and accountability, we have to examine our own prejudices and fight those prejudices within ourselves to bring justice for one another within our own communities. Belgium had control over Congo in the past, but it’s up to us to shape our future.

Additional reports : Photos by Danny Matsongani in Beni, Video by Justin Mwamba in Bukavu (DRC)