Bukavu and Kinshasa, May 27, 2020

Reading time:

7 min

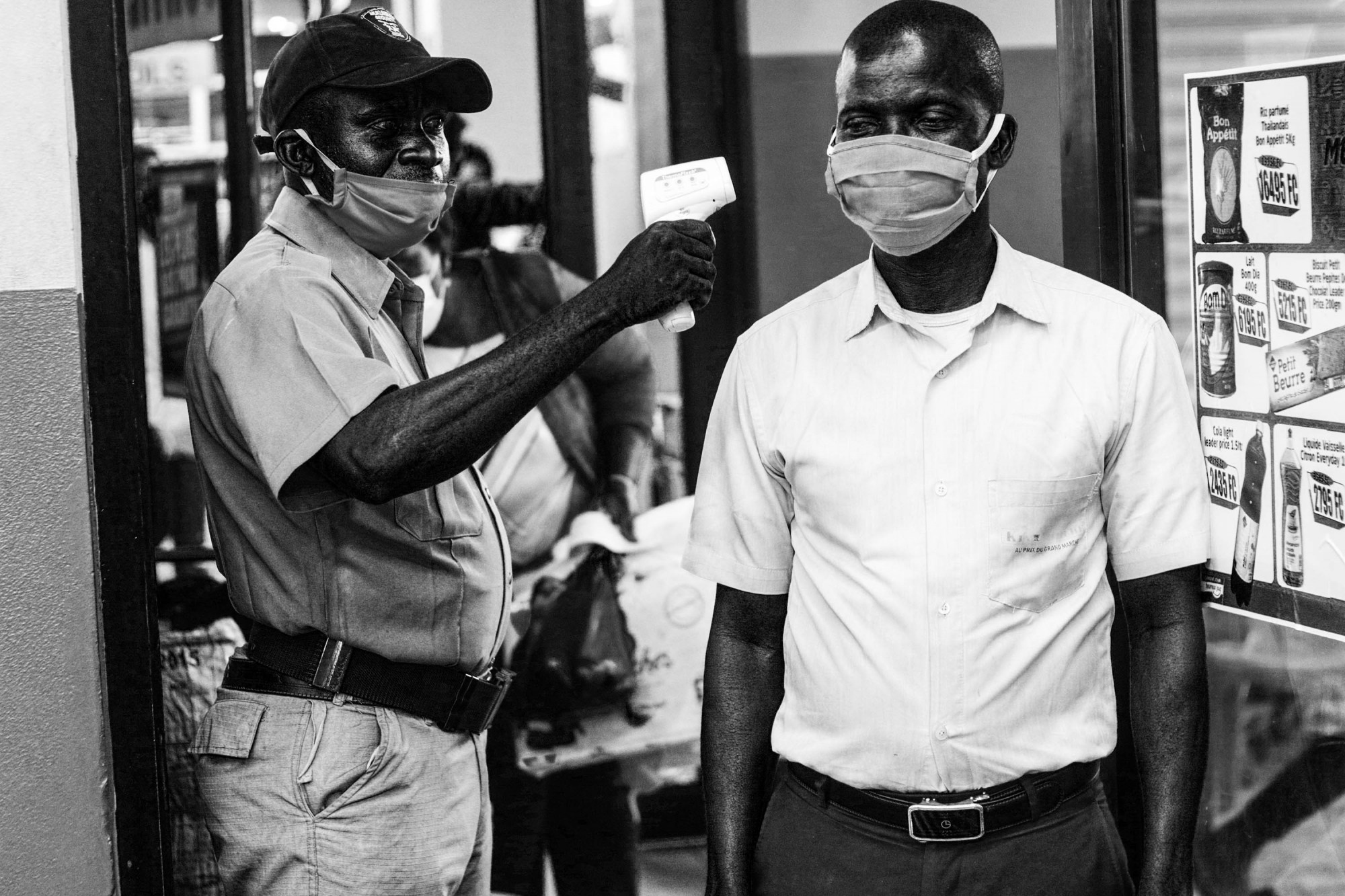

Congo’s coronavirus laws make wearing a mask mandatory in public. People must also respect social distancing measures, wash their hands before entering most buildings, and adhere to curfews and other guidelines determined by local or provincial authorities. Those who don’t follow the rules risk being fined by police, or worse.

Congo’s police have a longstanding reputation for harassment, corruption, and excessive use of force and most Congolese don’t trust them. Since the implementation of the new coronavirus rules, video footage has circulated on Twitter showing police violence in Kinshasa and Goma. In the Kinshasa incident, Sylvano Kasongo, who heads the Kinshasa police, is seen in a March 26 video appearing to order one of his officers to beat a taxi driver for violating a one-passenger limit, according to Reuters. The news agency reported that Kasongo sent them the video to encourage others to obey the rules. Congo’s police force respects human rights, Kasongo told Reuters.

Concerns are growing that police forces around the world are using gruelling and humiliating punishments to enforce quarantine on the poorest and most vulnerable groups, including those who risk starving if they do not defy lockdowns and seek work. UN human rights experts have urged countries to ensure their responses to the pandemic are “proportionate, necessary and non-discriminatory”.

After a confusing series of initial missteps dealing with the coronavirus outbreak in Kinshasa in March, Human Rights Watch called on Congo’s government to implement a robust communication plan to gain the people’s trust and to quickly put in place rights-respecting measures. “The survival of millions of people will depend on it,” Human Rights Watch said.

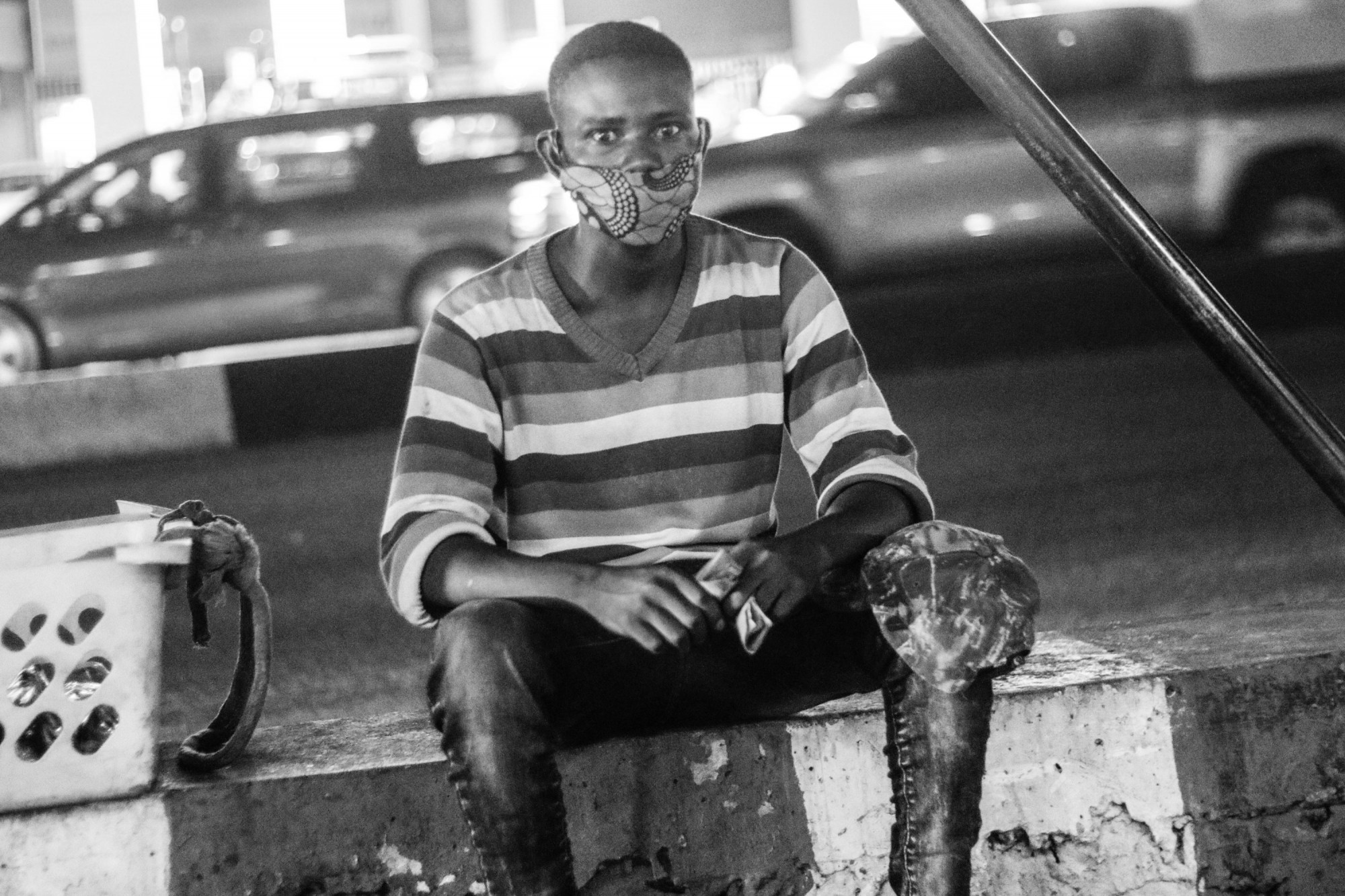

Since then, residents of Congo’s cities have grown accustomed to wearing masks outside, but as we photographed in Bukavu and Kinshasa, we saw many people carrying their masks, or exposing their faces, only keeping their masks handy to avoid being harassed and shaken down by police. Others, such as 29-year-old Bukavu fashionista Anglebert Maurice Kakuja, have made the mask part of their sartorial elegance. Such approaches are part of people’s ability to adapt to whatever situation we are experiencing.

Foreign agencies, governments, and anti-corruption bodies consider corruption immoral and a major barrier to development. That’s true, but it’s also an engrained part of life in many countries, including Congo. Police and taxi drivers in Bukavu, for instance, consider corruption a necessary condition for survival, according to a 2018 report in the Journal of Contemporary African Studies. “For them, corruption is a system that provides job security, greater access to food, accommodation, healthcare and education in the dysfunctional and failed Congolese State,” wrote Ali Bitenga Alexandre, the Congolese author of the report.

So by wearing masks, we are not only adapting to the latest health concern, we are acknowledging a reality of daily life in Congo.