In Congo—like in so many other countries, especially in Africa—light-skinned women are more ‘valued’ by society and are favoured over those with darker skin. This colorism and discrimination against people with darker complexions drive women to use harmful skin-lightening products to gain social and economic status. Skin bleaching is the process by which soaps, creams, pills, and injectables are used to reduce melanin concentration in the skin.

Skin lightening can be traced back to the 16th century, but it is now a lucrative cosmetic industry projected to be worth over $24 billion by 2027, according to Vogue magazine. This is despite warnings by the World Health Organisation that skin bleaching can cause liver and kidney damage, psychosis, brain damage in fetuses, and cancer. Countries as widespread as Ghana, Japan, Australia, and Rwanda, have banned the use of bleaching agents, but the WHO estimates that 40% of African women still use them.

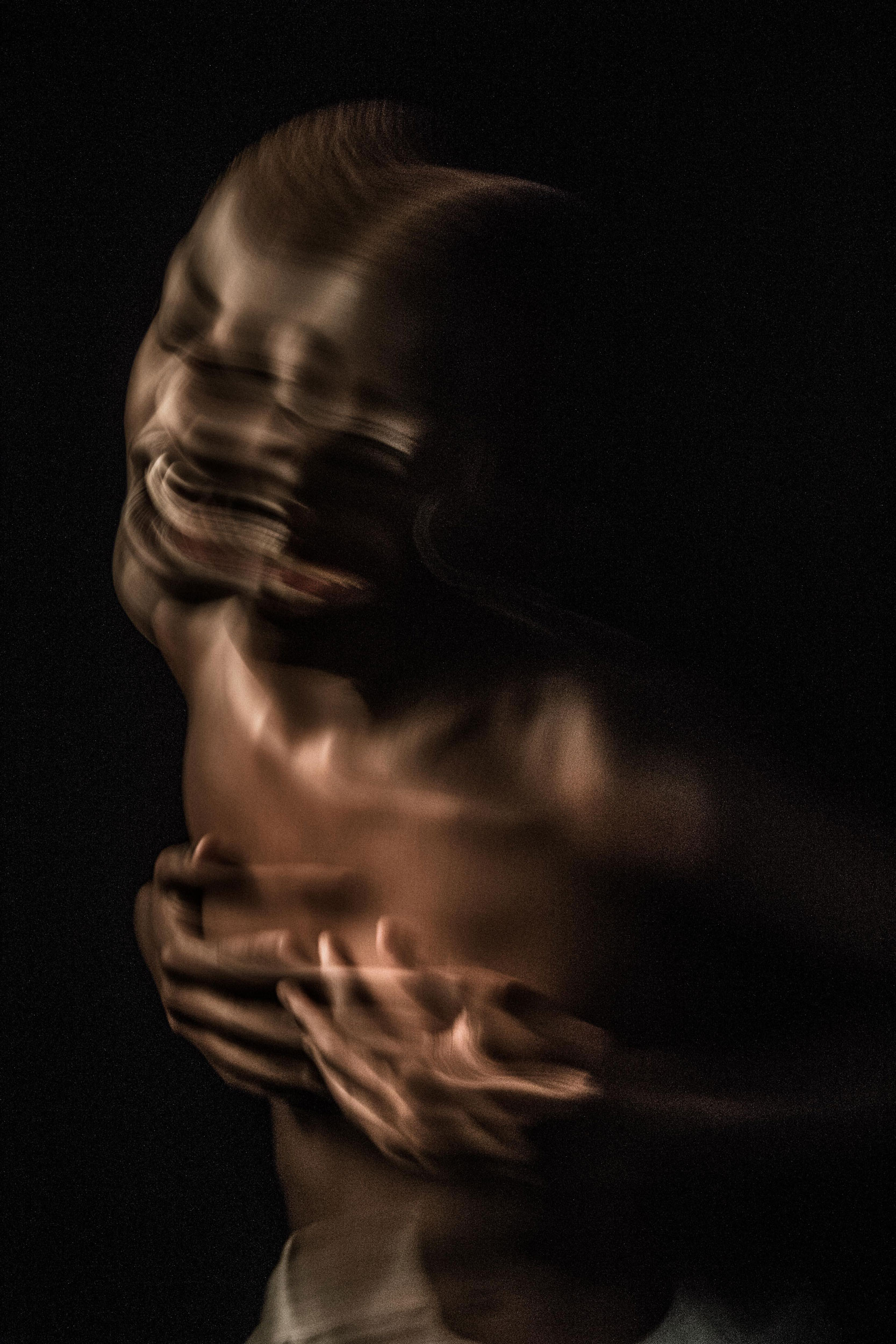

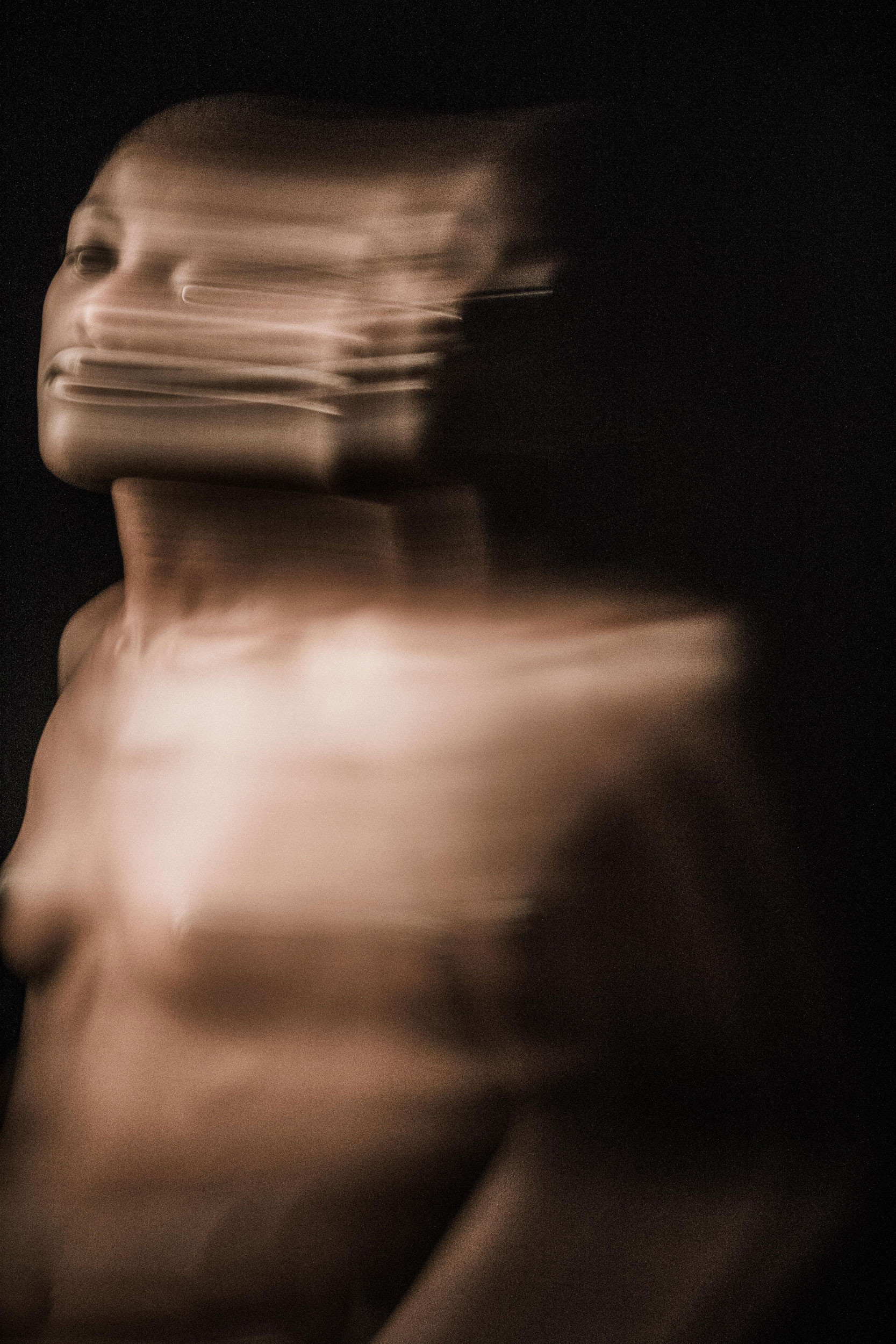

This work specifically condemns skin bleaching and more generally criticizes colorism. I exaggerate the blackness of the model’s skin to show the beauty of it. At the same time, she is trying to pull out of her skin because her blackness is devalued and dismissed by others. In each frame, part of the body is intentionally cut off, to symbolize that something is missing.

I made these images last year at the Market Photo Workshop, founded by David Goldblatt in Johannesburg, but I’m publishing them here for the first time. What struck me in South Africa is how confident the women are about their natural beauty. That’s what inspired me to begin this project. I’m still developing the work now during an artist residency in Brussels. Belgium is the country that colonized us, so being here gives me a lot to think about in terms of our Congolese identity.

The project addresses one aspect of our collective post-colonial psychology. There’s this mentality that whiteness or lightness means ‘better’—more intelligent, more beautiful, more evolved. It’s a kind of inferiority complex. On TV and on billboards, you see all these models with light skin and straight hair and they look so happy and confident.

These images are the exact opposite of that. They critique the social pressure for us to bleach our skin, to wear wigs or weaves, or to straighten our hair. I used to straighten my hair because I thought it was prettier. Then I realized I was colonizing myself.

The models had a shaved head. I wanted to show them completely natural: no wigs or hair products, just as we were born. Even the make-up is atypical—it goes against what is usually considered ‘beautiful’ by exaggerating the lips and facial features.

My interpretation is about a return to authenticity and to nature. Chemically lightened skin, wigs, and weaves have nothing to do with beauty. Beauty is when we assert ourselves and are natural and comfortable within our own skin.